Sharing of customer service and repair data has potential to lead to $2,500 fines per instance

Steven E. Schillinger is a P.E. and PBE consultant in addition to being “actively retired.” He can be reached at schillingersteven@gmail.com and linkedin.com/in/seschillinger.

In the midst of Covid-19, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) has already gone into effect as the first law in the U.S. for governing rules around consumer data, akin to the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

The new privacy laws apply to companies that operate in California with either $25 million in sales, more than 50,000 users, or makes more than half its money off of user data. For auto shop owners, it creates new liability over their service and repair data. The most significant is now consumers have “the right to know” and “the right to say no.” That means customers are able to see what information has been gathered about them, have that data deleted, and opt out of selling it to insurance companies, manufacturers or related organizations.

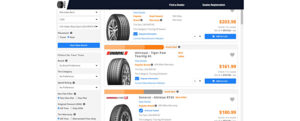

Most automotive aftermarket business owners indicate that they only use customer personal data internally, but some consumer information may go to third-party database providers, such as Mitchell, CCC and Audatex.

Since January, Californians have the right to sue companies for failing to take reasonable precautions to prevent data breaches. But apart from that, making sure businesses comply is the sole authority of the attorney general’s office, which has indicated that it should only need to bring a handful of cases each year.

The threat of crippling fines — $2,500 per user per piece of data, which could easily scale to the tens of millions for an organization that flouts the law — should be an effective deterrent.

— Alastair Mactaggart, board chair and founder of Californians for Consumer Privacy

For the average vehicle service and repair business in California, life will not be radically different. But as the procedures of the CCPA law get finalized for Covid-19, and depending on how it is enforced, its impact could go a long way to determining the future of shop owner liability.

Many vehicle manufacturers have already employed processes allowing European users to delete their data or opt out of tracking thanks to GDPR, which set some groundwork for CCPA and Covid-19. Some platforms, including Google and Facebook, have built tools allowing users to exercise the rights that California now guarantees to consumers.

Final regulations that clarify and define the parameters of the new laws have not been released, but California’s Attorney General Xavier Becerra is expected to issue them in conjunction with Gov. Gavin Newsom’s plan for reopening the state from coronavirus. California is not scheduled to start enforcing the laws until July 1.

Alastair Mactaggart, board chair and founder of Californians for Consumer Privacy, said, “I come from one of the most heavily regulated industries in the country: real estate development. I’ve literally never even come close to sitting in any meeting where I’ve heard anyone say something like, it’s the law, but we’re not going to get caught, so let’s just do it anyway.” He argued that even if cases are rare, the threat of crippling fines — $2,500 per user per piece of data, which could easily scale to the tens of millions for an organization that flouts the law — should be an effective deterrent.

Meanwhile, the CCPA and the Covid-19 laws may put pressure on Congress to act at the national level, as the automotive aftermarket cries at the prospect of complying with a patchwork of state requirements. (States like Nevada and Vermont have their own privacy statutes; lawmakers in other states, such as New York, have tried to introduce bills that are even more ambitious than California’s.) The Senate is considering a number of bills, but so far Democrats and Republicans are far apart on two key issues: whether to grant ordinary Americans the right to sue for violations (Democrats generally think yes, Republicans, no), and whether the federal law should preempt tougher state regulations (Democrats, no, Republicans, yes). The longer Congress waits to act, the more California — and any state that goes even further — will get to determine the facts on the ground.

Comments are closed.