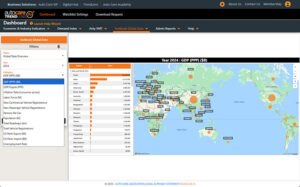

In the future, AI could be used to analyze sensor data and predict part failures before they occur, offering initiative-taking maintenance

The Las Vegas Convention Center during Industry Week is typically alive with the roar of muscle cars and the smell of high-octane fuel, but Jeff noticed that the exhibit areas were instead filled with silent, humming displays of onboard diagnostics, telematics and computer-driven systems.

At one booth, a representative for a new in-car network — labeled a digital “nervous system” — proudly explained how its technology would restrict access to vehicle data, reserving it exclusively for licensed, factory-certified technicians.

A chill went down Jeff’s spine. This was about more than diagnostics; it was about locking independent service and repair shops out of the system entirely. A simple wrench, he realized, would no longer fix a software glitch. This wasn’t just a change in technology; it was a technological chokehold on his livelihood.

An Alliance of the Unlikely

Jeff remembered that one of his customers had been struggling with a recurring electrical issue in a new vehicle, a problem his scanners simply could not diagnose. He called a friend at the dealership, who sheepishly admitted the new diagnostic software was proprietary and not shared. Frustrated and at a dead end, Jeff posted his problem on LinkedIn, Facebook and YouTube.

Eleanor Vance works for the Federal Bureau of Automotive Regulation. For years, her job has involved drafting and enforcing rules for safety, emissions and fuel efficiency. But as she walked through the exhibits, she recognized that the data-driven revolution was more than making cars safer and greener — it was a power grab for control.

Eleanor was searching for examples of technological barriers hindering automotive shops while she toured the convention center exhibits. Her search led her to the same forum where Jeff had been. Intrigued, she sent him a private message introducing herself.

Jeff was skeptical but desperate enough to agree to a video call. Eleanor listened intently as Jeff explained his predicament. She explained her own concerns about the industry’s direction. An unlikely alliance between Jeff and Eleanor resulted, united by the need to preserve an open market.

The Regulator’s Revelation

Eleanor saw the booth presentations, watching as automakers built digital fences around their vehicles’ information. She spoke with a supplier whose frustration was obvious. The supplier complained that without access to proprietary codes, obtaining parts was almost impossible.

Coincidently, she overheard a conversation between Jeff and a younger technician — a moment that reinforced her growing concern. They discussed how independent technicians were losing business to dealerships because they could not access the same proprietary information.

Eleanor realized the government’s role had to evolve. Regulations designed for a world of replacement parts were now obsolete. She envisioned a future where independent shops like Jeff’s would become relics.

A monopoly on repair would mean higher costs and fewer choices for consumers. She began to formulate a plan to protect auto shops. Energized by the growing “Right to Repair” movement, she listened to a gathering of independent shops and repair advocates.

Their strategy was simple but spirited: focus on what AI could not yet do. They would specialize in the “ghosts in the machine” — the problems that were too complex or obscure to solve.

The Lawmaking Battle

Eleanor began drafting legislation, dubbed the “Automotive Data Access and Repair Act.” It was not an easy sell; lobbyists from major manufacturers began contacting her office. They argued that providing proprietary data would compromise safety and intellectual property, claiming independent shops were not prepared for complex repairs and that only factory-certified technicians could perform them.

Meanwhile, Jeff became the public face of a movement. He started a popular video series called “What the Code Won’t Tell You.” He highlighted the frustrating situations faced by independent shops. His simple and heartfelt videos gained a massive online following, showing a knowledgeable technician forced to turn away customers simply because of a digital lock. This grassroots support, fueled by frustrated consumers, provided Eleanor with the public pressure she needed.

The turning point came during a congressional hearing. Jeff testified about the problem, showing a video of a car that was towed to his shop. He then displayed the incomprehensible code from the vehicle’s onboard computer.

“This,” he said, holding up a small, worn-out wrench, “used to be the tool for understanding. Now, this is what we have.” He held up his generic scanner, which could only read surface-level problems. “The dealerships have the full book. We just have the cover.”

Jeff’s shop became a case study for the success of a new model. His team, now certified “AI-Assisted Technicians,” used artificial intelligence to analyze sensor data and predict part failures before they occurred, offering initiative-taking maintenance. They were no longer just fixing vehicles; they were preventing breakdowns from happening, building long-term relationships with customers.

The government’s role had shifted from a clumsy regulator to a nimble facilitator, fostering an environment where innovation and human ingenuity could coexist. Artificial Intelligence became a job-enhancer, not a job-killer, and the independent shop became more essential than ever.

Epilogue

Jeff’s shop flourished. With the new regulations, he was able to invest in advanced training and software, and his team became specialists in the very technologies that had once threatened to put him out of business. He even partnered with a local community college, creating a pipeline to train the next generation of technicians.

Takeaway:

This automotive service and repair tale is not a story of death but one of evolution and resilience. While the rise of EVs and computer driven systems presents significant challenges, it also creates new opportunities.

For savvy managers that embrace new technologies, diversify their services, and invest in their workforce, the future is still positive. Meanwhile, auto shops that do not adapt will face increasing pressure from market trends and competitors.

There is no single “Federal Bureau of Automotive Regulation,” but the primary federal agencies that regulate the automotive industry are the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) setting Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS). Other relevant agencies include the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) for commercial vehicles and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) for consumer protection in auto sales.

Coauthored by Wade Riddering, CEO of Environmental Regulatory Compliance (ERC), a Registered Environmental Property Assessor (REPA) and Qualified as an Industrial Stormwater Practitioner (QISP), and Steven Schillinger, an accredited Professional Engineer (PE) often speaking at auto industry meetings about EPA, OSHA and Fire Marshal regulations.

Comments are closed.